Prior to playing Tetris Effect, I didn’t really understand the appeal of Tetris. I was too young to ever own a Game Boy, the console that many Tetris fans cite as where they first fell in love with the game, and although I owned a GBA, Tetris, with its rudimentary graphics and simple gameplay, always looked boring to 11 year-old me. It was a game that my otherwise non-videogame-playing dad had owned on the NES before I was born, a game that he often claimed was, in fact, the best that had ever been made, which, of course, immediately made it the most uncool game ever. Why would I want to play Tetris when I could play Pokemon Ruby, or Golden Sun, or Mario Kart?

This attitude – that Tetris just wasn’t for me – stuck. I tried challenging it a few times over the years. I had it on my Nintendo DS as a teenager but sold it. I had it on my iPod but preferred Vortex. I bought Puyo Puyo Tetris on the Switch just to play the Tetris mode, but I still didn’t get it, and in the end I began to get frustrated. Why was lining up blocks on a screen, especially annoyingly-shaped blocks that never seemed to align in the way I wanted them to, and which fell impossibly quickly as the game went on, considered fun? Why did Tetris appear alongside masterpieces like Half Life 2, Shadow of the Colossus and Ocarina of Time in lists of the greatest games ever made? I didn’t understand. I thought something was wrong with me. How could I say that videogames were my favourite hobby but not like Tetris?

But then I played Journey mode on Tetris Effect, the game’s equivalent of a single-player campaign, and something changed.

Still, though, it didn’t happen right away. I played the game first of all in VR and spent most of my time cooing over the audiovisual extravaganza I was immersed in. The actual Tetris was a distraction, and an uninteresting one at that – it was just Tetris, I thought. Tetris with some prettier colours and blocks that pulsed to a beat, but Tetris all the same, the game I’d tried multiple times before but had never understood. I actually went so far as to refund my purchase the first time around. I’d played it for less than two hours and I’d only bought it as I wanted to see what my newly-acquired Oculus Quest 2 could do, so once the novelty faded I got my money back.

However, something made me rebuy it (probably the renewed adulation that came about with the release of Tetris Effect: Connected) and I started Journey again. This time I saw it through and completed it on Easy mode, which turned out to not be that bad, after all, so I went back and completed it once more, pushing the difficulty up to Normal.

It took me until my third run through of the game, now on Expert, and until the final third of its ultimate stage, Metamorphosis (where the speed is set to maximum and blocks don’t drop so much as suddenly just appear at the bottom of the screen) for me to realise that I was having a fantastic time. It was only then that I understood the game’s beautiful simplicity, its undeniable eloquence, and I respected the way that it demanded my complete, unwavering attention. I had achieved a state of perfect flow, locked in the VR headset, my fingers moving faster than my brain could think. I was utterly enchanted, bewitched. In the zone.

At last, after what was only a handful of minutes but which felt like hours, as I cleared Metamorphosis’s ninetieth line and the credits began to roll, I was overcome with an immense feeling of gratitude towards this game, for the obvious amount of time and effort that had been put into each of its 30 stages, for the artistry of the music and the way that it synchronised with my every move, but, more than anything else, I was grateful for the fact that it was the game which had finally taught me how to enjoy Tetris.

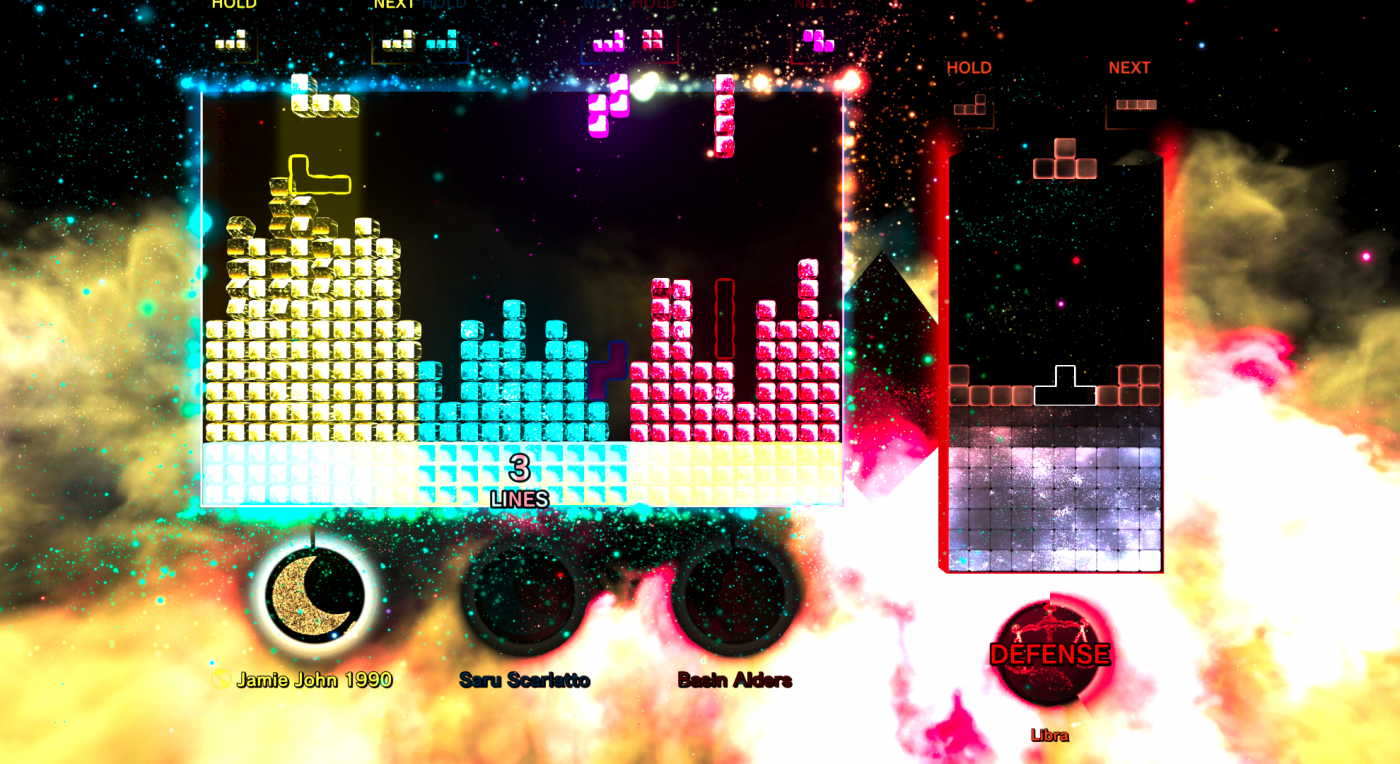

Since completing Expert mode, I’ve become a bit of a Tetris addict. I’ve played through Journey half a dozen times more and currently have another run going on my Quest. I’ve downloaded the Game Pass versions for Xbox and PC. I’ve tried out the multiplayer and have played co-op Tetris with different people from all around the world. I’ve had a go at the Effect modes, like Sprint, Ultra and Marathon, all of which have made me realise that I’m not, as it happens, very good at the game, but I’m determined to get better. I’ve redownloaded Puyo Puyo Tetris on my Switch so I can play Tetris handheld. I’ve got the official Tetris Android app so I can play it on my phone. My Youtube recommendations are full of Tetris tutorials, record attempts and interviews with world-class players. I play Tetris late into the night and see falling tetrominoes behind my eyelids. I can’t stop humming the tune to Korobeiniki, the 19th century Russian folk song on which the Tetris theme is based. It’s driving my wife mad.

So, for these reasons and more, I’d recommend Tetris Effect to anyone, but especially to those of you who don’t really get Tetris. If the sense of blessed relief that comes at the end of an I-block drought, or the profound satisfaction you’re met with when beating your previous Sprint time, are unknown sensations to you, then I urge you to play this game. It will make you understand.